archive

"Civil War Chicago: Eyewitness to History" on October 20th

Professor of History Theodore J. Karamanski, PhD and Loyola alumna Eileen M. McMahon, PhD, will discuss their new book on the Civil War’s transformative role in Chicago's development.

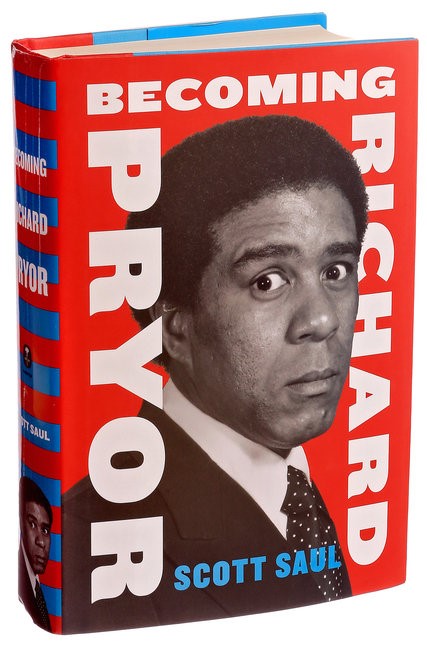

Richard Pryor Biographer to Speak at Loyola

Scott Saul, the author of Becoming Richard Pryor, will give a public lecture on the comedian entitled "Living with Richard Pryor: A Biographer's Tale" on Friday, April 24 at 3 PM.

Timothy Gilfoyle on "The Changing Forms of History"

Should history be a book discipline? What constitutes "acceptable scholarship" in history? Professor Timothy Gilfoyle considers the rich and diverse forms that historical scholarship take from books, digital media, and public history projects in his article "The Changing Forms of History" in April's edition of Perspectives on History, the AHA newsmagazine.

"The Rise of the Nation-Saint" on November 5th

Prof. Kathleen Sprows Cummings, University of Notre Dame, discusses a pre-circulated paper on the efforts of U.S. Catholics to secure their first canonized saint for the third meeting of the 2015-2016 Ramonat Seminar Series.

Voices of Chicago Women Activists

Celebrate Women's History Month with the Women & Leadership Archives and the Chicago Area Women's History Council. Come hear multimedia excerpts of oral histories by Columbia College honors students featuring Chicago women activists and leaders. The event will be held on Sunday, March 16th from 2:00pm-5:00pm on the 1st floor of Piper Hall.

What was Chrysler Village and how did it get its name?

Public History graduate students know and shared their work on a historic nomination for the neighborhood with Ask Geoffrey on WTTW the other night.

LEARN MORE

Closing the Gap

Sarah Doherty (PhD '12) reflects on the importance of the Preparing Future Faculty Program in equipping her, and other minority doctoral students, with the skills necessary for a career in academia.

LEARN MOREFrom Seminar Paper to Journal Article: A Recent Graduate's Experience

Doctoral student William Ippen recently caught up with recent Medieval History MA graduate Maria Wagner about her recent article "The Impact of the Second Crusade on the Angelology and Eschatology of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux," which appeared in the September 2013 issue of The Journal of Religious History.

Please tell us about your time studying at Loyola.

I obtained my Masters in Medieval History from Loyola from 2008 to 2012 on a part-time basis. Being a bit older than the “traditional” graduate student, I found the program challenging and fascinating as it gave me the opportunity to conduct historical research and write in a manner different than my earlier academic and employment experiences.

What was your recent article's genesis? What first drew you to your topic?

Thank you! I became interested in Bernard of Clairvaux after reading historical fiction about Eleanor of Aquitaine. As a fictional character in these stories, Bernard was frequently portrayed as interfering and critical, yet necessary to the events of the day. When I subsequently explored historical writing on Bernard, including his own works, I found him to be a significantly more complex character who has often been shortchanged in historical renderings, fictional and non-fictional.

Also, I became interested in eschatology after speaking with my father-in-law, Walter H. Wagner, Ph.D., who works on the subject at Moravian Academy and is pursuing interfaith understandings of the end of days and how they are complementary. Since Bernard had a significant amount to say on these matters, it was a natural blend of two interests.

Walt also encouraged me to send the article draft to a “big” journal, rather than journals for graduate students, for which I am very grateful.

With whom did you work on the project? How important was that relationship?

I primarily worked with Father John McManamon, which was truly a joy. His boundless patience and support were so helpful, not to mention the assistance he gave me in translating twelfth century Latin and connecting the pieces of my article into a fluid narrative. I am not sure that the article would have been accepted without him.

Tell us a little about your argument. Where does your article intervene in the historiography?

Bernard has often been characterized as dichotomous… a self-described “chimera.” On one hand, he was an adroit politician, impacting international events in Western Europe, including calling the Second Crusade, and on the other, he was an irenic monk, living in solitude and explicating the Song of Songs. My paper argues primarily against a recent dissertation that describes Bernard as despondent and ready to dispose of his prior beliefs in response to the failure of the Second Crusade. While I agree with the latter statement for the most part, I do not agree that Bernard was disheartened. Rather, I see him as returning to the optimism and inner serenity that characterized his early writings.

What was the most satisfying part of the project?

Completing it! No, really, it was very satisfying to work on it all throughout the process. In particular, I enjoyed having a few of those exciting moments of discovering bits of supporting evidence in primary sources that helped solidify my argument. They make all the hours of reading worth it.

Did you learn anything surprising or shocking?

One thing I learned that was surprising and a bit disappointing, honestly, was the frequent lack of accuracy in translations to English from medieval Latin. It made me wonder how prevalent this is in other translations. Even a very recent biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine contained an important “quote” from Bernard (in English) that was quite incorrect based on the original Latin, yet was used by the biographer to offer a significant (and in my opinion, incorrect) conclusion about the relationship between Bernard and Eleanor. The lesson I learned is to always go back to the original primary source to confirm any historian’s translations.

What were some challenges or obstacles? If you were to do it over again, what would you change?

In my case, my Latin was not nearly adequate enough to work through the primary sources alone, which is why I was and am so grateful for Father McManamon’s help. Other challenges included a lack of translated material (notwithstanding my point above!). I suspect that all scholars of Bernard wish for that one definitive English-language biography that might replace Vacandard’s La Vie de Bernard, Abbé de Clairvaux, which has not been translated from the French.

Do you have any advice for graduate students looking to get a seminar paper published?

Just do it! It cannot ever hurt and can only help a paper to actually submit it for critique. The journal’s reviewers will provide constructive criticism of the paper, and the editors will often offer the scholar an opportunity to revise and resubmit the work. It’s so exciting and gratifying to see one’s work published, and to add to the historiography of a topic one enjoys--it is definitely worth the risk!