Establishing Learning Outcomes

Overview of Course Learning Outcomes

In the first stage of the backward course design process, we wanted to think about what students will learn – what they should be able to think, do, or say at the conclusion of a course. Now we want to turn those ideas into learning outcomes. Learning outcomes, or the desired results of learning, are specific and observable statements about what students will be able to do or say at the end of the course. Learning outcomes delineate what kinds of knowledge, attitudes, and skills students will be able to demonstrate in observable ways to prove they have learned something. Good learning outcomes let students know what they should learn and how that learning will be useful to them.

Writing learning outcomes helps us organize the course as we identify the key concepts and "big ideas” we want students to learn. Here are some guiding questions to keep in mind as we think about learning outcomes.

- What big ideas do we want students to walk away with when the course is over?

- What do we want students to remember about the course five years from now?

- What do we want students to know, say, or do at the end of the course?

Answering these guiding questions as we write the learning outcomes helps us plan instruction.

What are some examples of learning outcomes?

The table shows examples of learning outcomes that are measurable

|

Learning Outcomes that are Measurable |

|

Describe how the process of photosynthesis works |

|

Explain the relationship between economics and poverty in third world countries |

|

Use the tenets of psychodynamic theory to assess a client in crisis |

|

Show how ethical dilemmas are evident in a case study about student leadership |

What makes these outcomes measurable? The outcomes:

- Delineate what actions or skills students will demonstrate: Describe, explain, use, show

- Use active verbs that are easy to measure: Describe, explain, use, show

- Delineate conditions under which actions and skills should be accomplished so that it is easier to determine if the outcome has been achieved (e.g., in third world countries, a client in crisis, a case study about student leadership).

As a contrast, the table shows examples of learning outcomes that are not measurable

|

Learning Outcomes that are Not Measurable |

|

Understand the process of photosynthesis |

|

Explore the relationship between economics and poverty |

|

Acquire familiarity with the tenets of psychodynamic theory |

|

Learn about ethical dilemmas by reading and discussing a case study |

Why aren’t these outcomes measurable? The outcomes:

- Do not delineate how students will actually demonstrate understanding, exploration, acquisition, or learning

- Do not use active verbs that are easy to measure: How will students and instructors know if they are able to understand, explore, acquire, or learn? All of these terms are too vague and general to be effectively assessed.

- Do not delineate conditions under which actions and skills should be accomplished: Without specifying when or how the outcome will be achieved, it is more difficult for students and instructors to know if they have achieved the outcome.

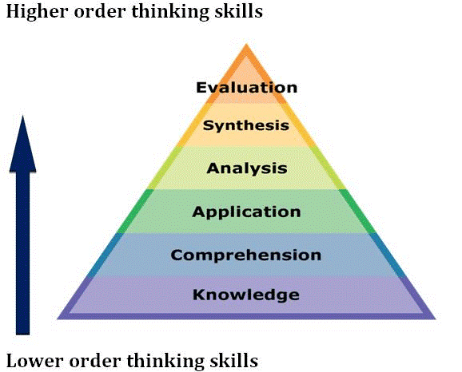

Bloom’s Taxonomy

In most courses, we want students to learn on many different levels – to remember, understand, apply, analyze, synthesize, evaluate and more. One tool that can help us think through what levels of learning we want to achieve in our courses is Bloom’s Taxonomy, developed by educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom. As seen below, Bloom’s Taxonomy illustrates different levels of thinking, from lowest to highest. The levels of thinking are associated with verbs that describe measurable actions. Using Bloom’s Taxonomy as a guide when writing learning outcomes helps us ensure that we include a variety of activities and content in the course to challenge students to use lower-order and higher-order thinking skills.

Image of Bloom's Taxonomy

How do you write learning outcomes?

A simple three-step process can make writing learning outcomes easy:

- Start with the verb. Decide what actions or skills students should demonstrate. Use active verbs that are easy to measure by using Bloom’s Taxonomy.

- Follow the verb with a statement that outlines what knowledge or skill students should demonstrate. In the first example below, the student is demonstrating knowledge of how the process of photosynthesis works.

- Determine the conditions under which actions and skills should be accomplished.

Writing Learning Outcomes Sets the Stage for Alignment

A key premise of backward design is that there is alignment between the desired results, acceptable evidence, and plan for instruction. Here is an example of alignment between the learning outcome the instructor has created, the method of assessing whether the student has achieved the outcome, and the learning activities that will help insure the student does learn the content.

|

Alignment |

||

|

Identifying desired results (e.g., learning outcomes) |

Determine acceptable evidence (e.g., assessment) |

Learning and instruction (e.g., learning activities) |

|

Describe how the process of photosynthesis works

|

Create an accurate illustration of process of photosynthesis |

Read about photosynthesis Watch presentations that illustrate the process of photosynthesis |

You can see from this example that creating an accurate illustration is how students will demonstrate that they can describe how photosynthesis works. The reading and video explain what photosynthesis is and how it occurs so that students can learn this specific course material.

Here is an example of an absence of alignment.

|

Absence of Alignment |

||

|

outcome |

assessment |

activity |

|

Describe how the process of photosynthesis works

|

Write a research paper that evaluates how different physiological factors influence photosynthesis rates |

Read a general overview of photosynthesis |

You can see from this example that writing a research paper that evaluates different factors that influence photosynthesis rates may not allow students to demonstrate that they can describe photosynthesis. Or, assigning a research paper may presume students can describe photosynthesis, when they may not be able to; this assessment may never allow the teacher to really know if students have achieved the learning outcome. Additionally, the assigned reading will not prepare students to write the research paper.

When the course design process begins with establishing learning outcomes, then we can determine assessment strategies that are a good fit for gathering evidence of students’ ability to demonstrate the learning outcome. We can also select activities that will adequately prepare students to complete the assessments. The next sections of the guide focus on determining assessment strategies and selecting activities.

References

- Enduring Understandings. Retrieved from iTeachU UAF eLearning & Distance Education.

- Teaching and Learning Frameworks. Retrieved from Yale University Center for Teaching and Learning.

- McTighe, J., & Wiggins, G. (2012). Understanding by design framework. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Writing Intended Learning Outcomes Retrieved from Yale University Center for Teaching and Learning.

How to Write and Assess Program Learning Outcomes

Writing Program Learning Outcomes

Assessing Program Learning Outcomes

Overview of Course Learning Outcomes

In the first stage of the backward course design process, we wanted to think about what students will learn – what they should be able to think, do, or say at the conclusion of a course. Now we want to turn those ideas into learning outcomes. Learning outcomes, or the desired results of learning, are specific and observable statements about what students will be able to do or say at the end of the course. Learning outcomes delineate what kinds of knowledge, attitudes, and skills students will be able to demonstrate in observable ways to prove they have learned something. Good learning outcomes let students know what they should learn and how that learning will be useful to them.

Writing learning outcomes helps us organize the course as we identify the key concepts and "big ideas” we want students to learn. Here are some guiding questions to keep in mind as we think about learning outcomes.

- What big ideas do we want students to walk away with when the course is over?

- What do we want students to remember about the course five years from now?

- What do we want students to know, say, or do at the end of the course?

Answering these guiding questions as we write the learning outcomes helps us plan instruction.

What are some examples of learning outcomes?

The table shows examples of learning outcomes that are measurable

|

Learning Outcomes that are Measurable |

|

Describe how the process of photosynthesis works |

|

Explain the relationship between economics and poverty in third world countries |

|

Use the tenets of psychodynamic theory to assess a client in crisis |

|

Show how ethical dilemmas are evident in a case study about student leadership |

What makes these outcomes measurable? The outcomes:

- Delineate what actions or skills students will demonstrate: Describe, explain, use, show

- Use active verbs that are easy to measure: Describe, explain, use, show

- Delineate conditions under which actions and skills should be accomplished so that it is easier to determine if the outcome has been achieved (e.g., in third world countries, a client in crisis, a case study about student leadership).

As a contrast, the table shows examples of learning outcomes that are not measurable

|

Learning Outcomes that are Not Measurable |

|

Understand the process of photosynthesis |

|

Explore the relationship between economics and poverty |

|

Acquire familiarity with the tenets of psychodynamic theory |

|

Learn about ethical dilemmas by reading and discussing a case study |

Why aren’t these outcomes measurable? The outcomes:

- Do not delineate how students will actually demonstrate understanding, exploration, acquisition, or learning

- Do not use active verbs that are easy to measure: How will students and instructors know if they are able to understand, explore, acquire, or learn? All of these terms are too vague and general to be effectively assessed.

- Do not delineate conditions under which actions and skills should be accomplished: Without specifying when or how the outcome will be achieved, it is more difficult for students and instructors to know if they have achieved the outcome.

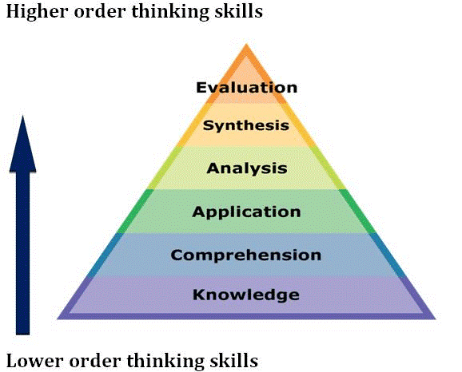

Bloom’s Taxonomy

In most courses, we want students to learn on many different levels – to remember, understand, apply, analyze, synthesize, evaluate and more. One tool that can help us think through what levels of learning we want to achieve in our courses is Bloom’s Taxonomy, developed by educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom. As seen below, Bloom’s Taxonomy illustrates different levels of thinking, from lowest to highest. The levels of thinking are associated with verbs that describe measurable actions. Using Bloom’s Taxonomy as a guide when writing learning outcomes helps us ensure that we include a variety of activities and content in the course to challenge students to use lower-order and higher-order thinking skills.

Image of Bloom's Taxonomy

How do you write learning outcomes?

A simple three-step process can make writing learning outcomes easy:

- Start with the verb. Decide what actions or skills students should demonstrate. Use active verbs that are easy to measure by using Bloom’s Taxonomy.

- Follow the verb with a statement that outlines what knowledge or skill students should demonstrate. In the first example below, the student is demonstrating knowledge of how the process of photosynthesis works.

- Determine the conditions under which actions and skills should be accomplished.

Writing Learning Outcomes Sets the Stage for Alignment

A key premise of backward design is that there is alignment between the desired results, acceptable evidence, and plan for instruction. Here is an example of alignment between the learning outcome the instructor has created, the method of assessing whether the student has achieved the outcome, and the learning activities that will help insure the student does learn the content.

|

Alignment |

||

|

Identifying desired results (e.g., learning outcomes) |

Determine acceptable evidence (e.g., assessment) |

Learning and instruction (e.g., learning activities) |

|

Describe how the process of photosynthesis works

|

Create an accurate illustration of process of photosynthesis |

Read about photosynthesis Watch presentations that illustrate the process of photosynthesis |

You can see from this example that creating an accurate illustration is how students will demonstrate that they can describe how photosynthesis works. The reading and video explain what photosynthesis is and how it occurs so that students can learn this specific course material.

Here is an example of an absence of alignment.

|

Absence of Alignment |

||

|

outcome |

assessment |

activity |

|

Describe how the process of photosynthesis works

|

Write a research paper that evaluates how different physiological factors influence photosynthesis rates |

Read a general overview of photosynthesis |

You can see from this example that writing a research paper that evaluates different factors that influence photosynthesis rates may not allow students to demonstrate that they can describe photosynthesis. Or, assigning a research paper may presume students can describe photosynthesis, when they may not be able to; this assessment may never allow the teacher to really know if students have achieved the learning outcome. Additionally, the assigned reading will not prepare students to write the research paper.

When the course design process begins with establishing learning outcomes, then we can determine assessment strategies that are a good fit for gathering evidence of students’ ability to demonstrate the learning outcome. We can also select activities that will adequately prepare students to complete the assessments. The next sections of the guide focus on determining assessment strategies and selecting activities.

References

- Enduring Understandings. Retrieved from iTeachU UAF eLearning & Distance Education.

- Teaching and Learning Frameworks. Retrieved from Yale University Center for Teaching and Learning.

- McTighe, J., & Wiggins, G. (2012). Understanding by design framework. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Writing Intended Learning Outcomes Retrieved from Yale University Center for Teaching and Learning.