New Jefferson Village

In with the new Jefferson Village, out with the old Jefferson Village

Detroit has a long history of conducting large-scale development projects using eminent domain to clear the needed land. Aside from highway construction, Detroit’s use of eminent domain tended to be large in scale and was often criticized for targeting poor and minority communities. The city’s 1946 Master Plan led to the razing whole blocks of houses and stores. It also was criticized for racial bias, displacing many African-American residents and businesses out of districts such as Black Bottom and Paradise Valley[1]

In contrast to earlier development strategies of clearing areas to make way for roads, industrial expansion, and downtown buildings, the Detroit’s development priorities have changed. Years of massive loss of population and jobs to the suburbs, has meant that attracting middle-class residents and jobs back into Detroit have become top priorities. The Jefferson Village project not only aimed at building new housing to bring middle-class homeowners back in, but it did it by building a suburb-like enclave in the city.

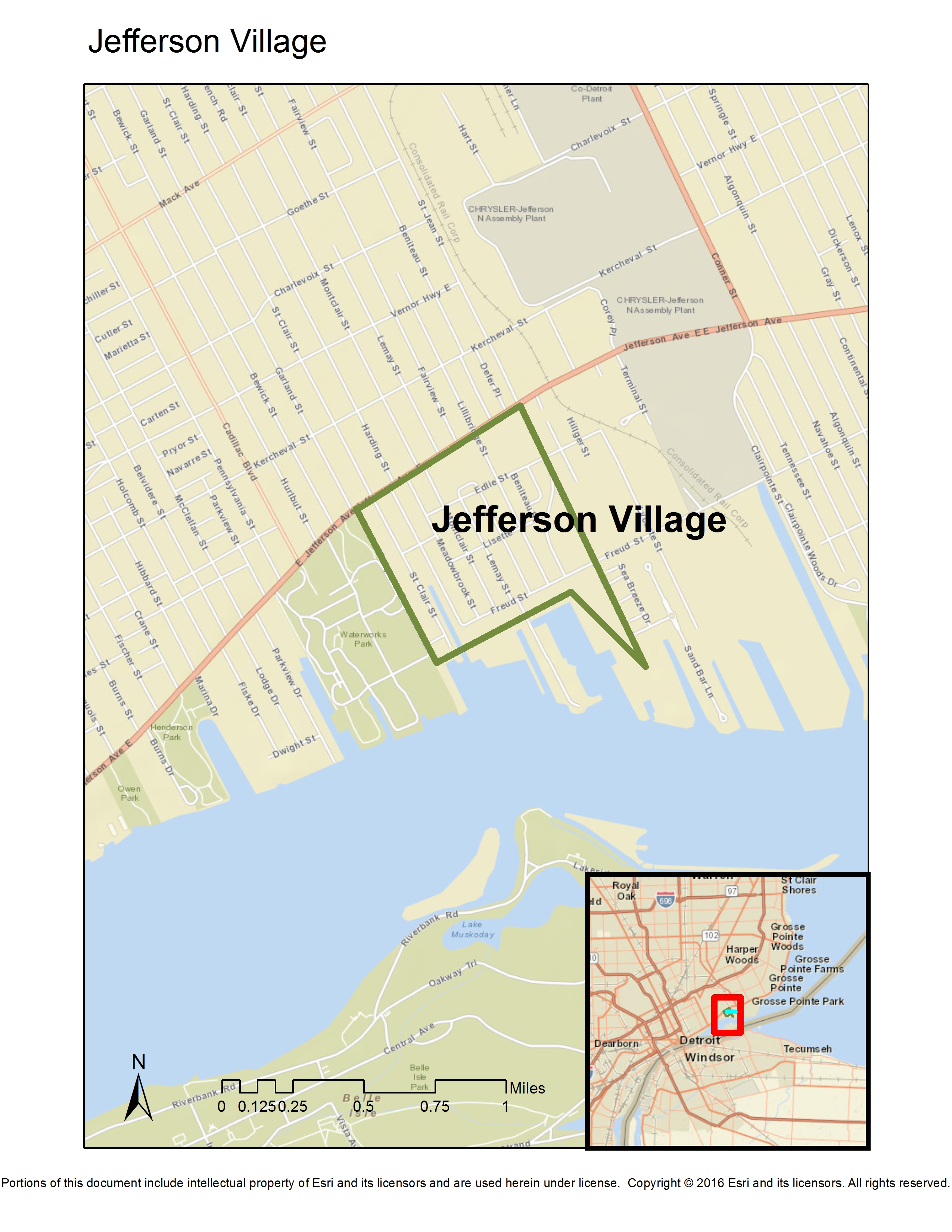

Jefferson Village was a new development in Detroit’s Marina District, bounded by Marquette Drive on the west, Engle Street on the east, the Detroit River on the south, and Jefferson Avenue on the north. The brainchild of Graimark Realty Advisors in 1995, they approached a number of city officials regarding a possible redevelopment project. Initially, Graimark wanted the City of Detroit to condemn and demolish all the buildings in the area to have a clean slate on which to build. Their proposal was to build over 400 homes in this 88 acre area.[2]

While interested, the City initially did not take any formal action and did not use its power of eminent domain to help Graimark bundle adjacent properties for the development. So between 1995 and 1997, Pulte Home Corporation, Graimark Realty Advisors, and a holding company created specifically to purchase land for the Jefferson Village project bought properties in the area through the normal real estate market. However, in March 1998, Detroit City Council did finally approve the Jefferson Village proposal. This provided $33 million for infrastructure improvements, as well as the acquisition, relocation, and demolition of properties in Jefferson Village. Eminent domain powers were used to condemn and force the sale of properties in instances where homeowners did not voluntarily sell. A joint group of private, public, and quasi-public entities would manage the project.

It is worth noting that Pulte Home Corporation was the largest home builder in the United States at the time.[3] Pulte got its homebuilding start in the early fifties in Detroit’s suburbs. Its growth corresponded with the post-World War II suburbanization boom across the country. Their role in bringing a suburban-like development to hollowed-out downtown Detroit in the 21st century is even more significant when one considers this background.

Questions about improprieties in the City’s contract award were raised by residents at the time. First, they challenged the City’s use of its powers of eminent domain and then turn the land over to a private developer. Second, they questioned the award of award of the contract without a competitive bid process. Charges of impropriety were fueled with personal connections between Mayor Dennis Archer and Graimark President Charles Allen. According to a Detroit Free Press article at the time “Archer’s son, Dennis Archer Jr., works for Allen, and his sister-in-law, C. Beth DunCombe, did legal work for Allen while in private practice. She now heads a quasi-public development agency that is helping oversee the Graimark project.”[4] These early challenges by the residents were not successful in stopping or slowing down the project.

Even though priced at what some national observers would see as modestly-priced homes, expected to average between $135,000 and $155,000, the new homes would be beyond the reach of most of the low-income homeowners and renters living in the Jefferson Village area before the redevelopment. The annual median income of the neighborhood was $20,000. Most of these individuals were renters. In 1998, only 68 of the 640 people living in Jefferson Village were homeowners. Eighty-six percent of the neighborhood population was African American and 10% was white. Of the homeowners, some lived in the community for decades. Clarence Henderson, 94 years old and a resident who lived on the same street in Jefferson Village since 1923, addressed city officials in his 2000 interview with the Detroit Free Press: “I hope they can find in their later years just what this does to people—this sudden yank-up, pull them up by their roots [emphasis added].”[5] Independent projections estimated that none of the current residents would be able to afford the new homes. Indeed the first 18 residents who attempted to prequalify for a loan were rejected.[6]

Even before the City approved its plan, the community had already been emptying out. This was not unlike other Detroit communities that had experienced depopulation. Before the 1998 City plan was instituted half of the neighborhood properties were already vacant and owned by the city due to tax foreclosures. As early as 1997, tenants of buildings that had been bought by Graimark’s holding company, Lemay Development Corp. had begun receiving eviction notices. Since these evictions were in the private market and not, at that time, associated with any city-initiated condemnation proceedings, tenants were not eligible for relocation benefits.

The redevelopment process proved to be contentious. At first the City and developers stated that they would be supportive of existing residents’ needs in the redevelopment process. The president of Graimark stated “We’re going to break our backs to accommodate as many of the existing residents down there that we can.”[7] However, one year later, residents were still protesting that the city had provided little information and no mechanisms to handle relocation benefits for affected residents, prompting an apology from a mayoral aide who acknowledged that the city had done a poor job communicating with residents.[8] Finally, 18 residents of Jefferson Village brought a suit against the City of Detroit, Graimark, and the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation (the quasi-public entity with strong developer ties who manages the project) arguing that the project provided “no public purpose and no necessity for the taking” through the eminent domain process.[9] The lawsuit was later settled out of court with residents opting to take payments for their properties.

Residents question whether every single property in Jefferson Park was really needed for this development to work. Professor of Urban Studies at Wayne State University Gary Sands questions the development plan:

"It was never at all clear to me why the City had to have every single parcel in that particular neighborhood. Most of the homes that were holding out were in fact fairly nice. They were older and in some cases the outside belied their interiors, which were quite nice. I would be very reluctant to give up a home where I could park my boat in the backyard. So, I can see why people don't want to leave. But, I was never convinced that it was absolutely essential that everybody leave the neighborhood. They could've worked around this."

[1] J.C.Reindl. “Detroit Planners Try a Softer Approach to Urban Renewal,” Detroit Free Press, February 10, 2013.

[2] Jennifer Dixon. “Displaced Residents Cry Foul: Probe Set, HUD Will Investigate Failure to Compensate.” Detroit Free Press, October 7, 1997.

[3] Jennifer Dixon, “Divided Council Oks New Homes for Detroit.” Detroit Free Press, March 21, 1998.

[4] Dixon, March 2, 1998.

[5] Jennifer Dixon, “Development sparks uncertainty,” Detroit Free Press. March 2, 2000.

[6] Jennifer Dixon, “Old Houses or New Ones? Detroit Plan Would Redo 88 Acres: Some Residents Balk.” Detroit Free Press, March 11, 1998.

[7] Dixon, March 21, 1998.

[8] Jennifer Dixon, “Residents Forced to Move Want Answers: Project Stirs Anxiety on Detroit’s East Side.” Detroit Free Press, February 13, 1999.

[9] Jennifer Dixon, “Residents Sue City to Keep Property,” Detroit Free Press, August 5. Detroit Free Press August 5, 1999.