Wall Street of Pre-Contact America

Celilo Falls was a 12-mile stretch of the Columbia River that contained a series of waterfalls and rapids. The Native American name for the area is “Wyam,” which is said to mean “echo of falling water” in several Native American languages.[1] Native American settlements, fishing, and trading villages were located here. The Falls were about 100 miles east of Portland, and 10 miles east of the town of The Dalles, Oregon. The abundant fishing available at Celilo made it an economic and cultural hub for native tribes in the region for thousands of years. An estimated fifteen to twenty million fish passed through the falls every year making it one of the continent’s most prolific fishing spots.

Native Americans had been living here for at least 12,000 years, making it the longest continually inhabited community in North America.[2] It was a hub of trading activity for multiple Native American tribes; in 1805 when the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed through this area, 5,000 people were routinely gathering here and engaged in a robust regional trading economy.[3] Charles Hudson, Director of Government affairs at Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) and a member of the Hidatsa Tribe from the Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold, North Dakota, explains that among Native American historians and anthropologists, Celilo had gotten the name as the “Wall Street of Pre-Contact America”:

"[D]ue to the local weather and geography, constant wind runs through that area. During the Salmon runs—March to October, it’s typically hot wind. This allowed for the natural drying/preserving of fish. …[T]he men would harvest fish, the women would prepare them for drying, and the hot wind would dry them and naturally preserve them. That would lighten them and allow them to be shipped more efficiently. It was the perfect nexus of a place to catch fish, preserve them and trade them…."

Portland State University historian Katrine Barber, underscores the importance of Celilo and the river to Native Americans over the millennia:

"The river was a supermarket, highway, and defense barrier. It was the center of a seasonal journey through fishing and gathering grounds that included netting and spearing salmon; gathering wild carrots, camas bulbs, and berries; and hunting deer and elk. Salmon shaped Native labor practices, and its significance was woven into language, ceremony, and story.[4]"

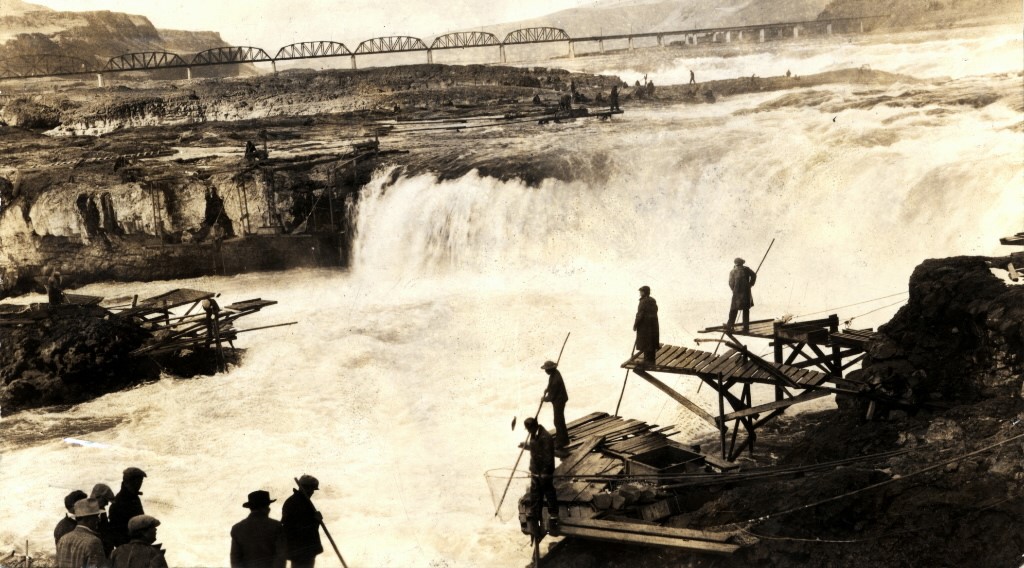

Barber describes the distinctive fishing practices of Native Americans, using scaffolds and platforms to catch fish during seasonal salmon runs:

"When salmon migrated, fishers waited on scaffolds that hung from cliffs above the roaring water of the falls or on platforms that reached out over the river like pointed fingers. From these cantilevers, Indians lowered mobile and stationary nets deep into the water where millions of salmon forced their way up the river. The rushing current pushed fish backward, stunning them and allowing Indians to skillfully scoop up the fish in their dip nets.[5]"

As noted by Wilbur Slokish, the sound of the falls themselves had religious meaning to members of the Celilo-Wyam Native American community. As noted above “Wyam” is said to mean “echo of falling water.”[7] It has been referenced many times by Native Americans recounting what was lost at Celilo Falls. A 1933 Civilian Conservation Corp newsreel (link below) is used by the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) to show active fishing along the river by members of the Yakama, Umatilla, Warm Springs, and Nez Perce tribes among others. CRITFC notes that “It is unclear whether the background sound [of waterfalls] during this segment was recorded at Celilo Falls, but if it was, it is the only audio recording of the mighty roar of the falls that CRITFC researchers have been able to discover.”[8]

© Richard Wasserman, 2011

[1] Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC), “Celilo Falls,” Website. http://www.critfc.org/salmon-culture/tribal-salmon-culture/celilo-falls/ Accessed February 14, 2016.

[2] Confluence Project, “Confluence Project Journey Book,” 2014. http://journeybook.confluenceproject.org/# Accessed February 18, 2016.

[3] Joe Rojas-Burke, “Sonar shows Celilo Falls are intact.” The Oregonian. November 27. 2008. http://www.oregonlive.com/news/index.ssf/2008/11/sonar_shows_celilo_falls_are_i.html. Accessed February 14, 2016.

[4] Katrine Barber, Death of Celilo Falls. Seattle:University of Washington Press, 2005, p. 23-24.

[5] Barber, p. 23.

[6] Rojas-Burke.

[7] CRITFC. “Celilo Falls”

[8] CRITFC, “Celilo Falls”