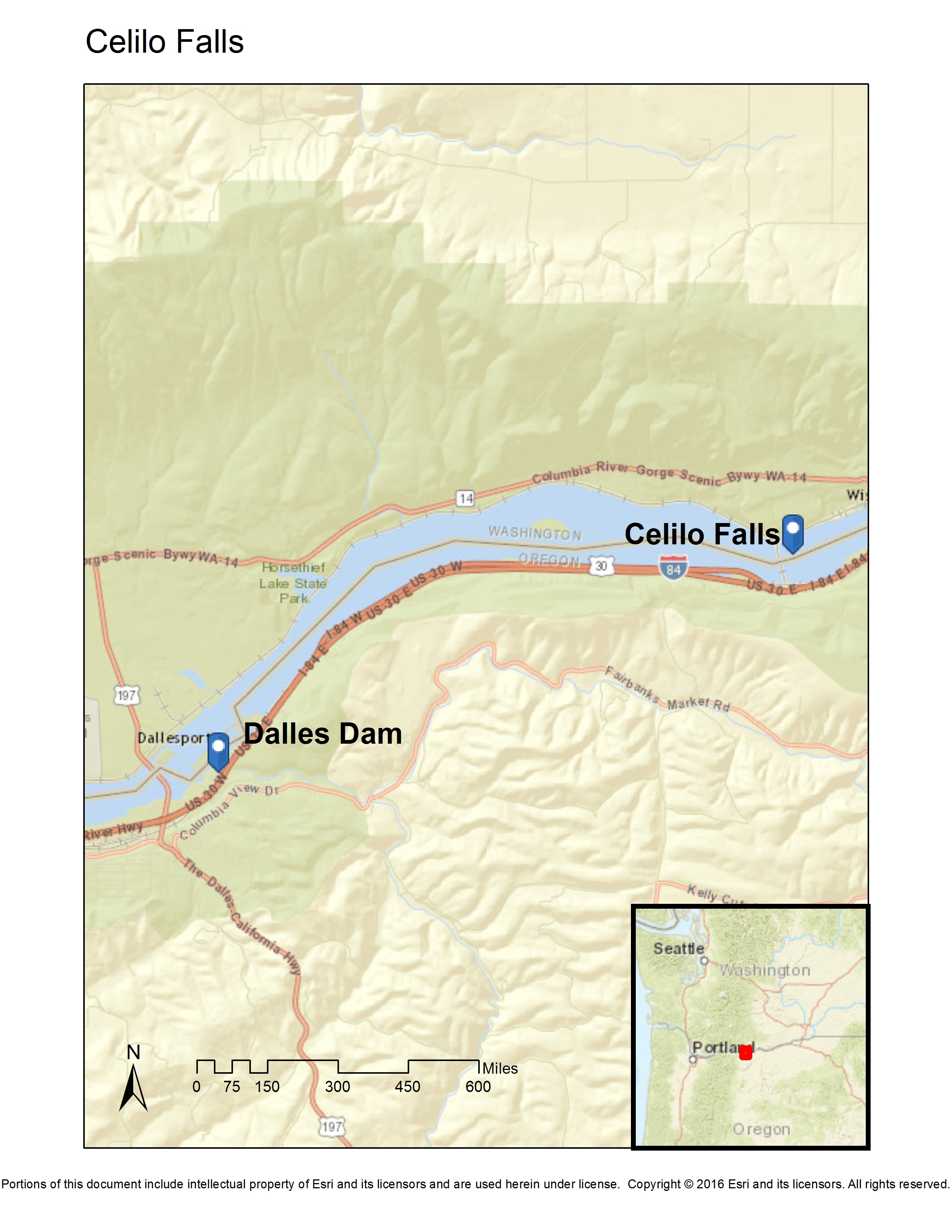

Celilo Falls, OR

The Mighty Columbia, Sacred Lands, and Eminent Domain

I miss hearing the sound of it. I miss hearing the sound of the falls. I was in New Mexico once, and I was by the dam, because the water comes over the falls. And I put a blanket there and I listened to that sound of that falling water. And it wasn’t as loud as Celilo. But a park ranger came over and asked me if I was okay. And I said I was listening to the falls. He said, “Oh, you must remember Celilo.” And I say, yeah, but it’s not as loud as Celilo. I remember looking back, being a kid and hearing those sounds….

Wilbur Slockish, Member of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation

The building of The Dalles Dam on the Columbia River in 1957 and the resulting submerging of Celilo Falls and the town of Celilo—places central to Native Americans for thousands of years—produced eminent domain clashes at multiple levels.[1] There was a clash between a modern, industrialized society and sacred Native American lands and practices. There were disagreements between furthering economic “progress,” on the one hand, and preserving memories and cultural traditions, on the other hand. It was a battle between forces wanting economic progress and others wanting to preserving nature.

As with other eminent domain sites, there were the studies by experts, the cost/benefit analyses, and the government hearings. In the end, the experts’ calculated arguments about furthering economic progress in the region won out. These arguments trumped sacred lands, nature, and memories. In the case of The Dalles Dam, the secular force of “progress” won out as it did previously in the building of the Bonneville Dam in 1937 and the Grand Coulee Dam in 1942. These dams, the renewable energy that they produced, and the progress they brought were celebrated by one of the nation’s most famous folk singers, Woody Guthrie. This is the same man who wrote that “This land is my land, this land is your land” in a song that has become a shadow national anthem.

However, in the 1930s, Guthrie, along with workers and industrialists, was also caught up in the celebration of industrial growth and economic prosperity. In climbing out of the misery of the Great Depression, economic progress took the lead sometimes to the detriment of nature and sacred lands. In “Roll on Columbia, Roll On” Guthrie celebrated the taming of the Columbia River, singing that the electrical power from its new hydro-electric dams were “turning our darkness to dawn, Roll on, Columbia, roll on.”[2] But the taming of the Columbia River didn’t stop with the Bonneville Dam, the economic and political forces continued to build dams. With the help of eminent domain in the 1950s, more lands were taken to further capture the productive forces of the Columbia and allow us to roll on over what had been important Native American lands—both in terms of sacredness and in terms of the economic health of the Native American community.

[1] “The Dalles,” including “The,” is the proper name of the city.

[2] Woody Guthrie, “Roll On Columbia” Words by Woody Guthrie, Music based on “Goodnight Irene” (Huddie Ledbetter and John Lomax). New York & Los Angeles:Woody Guthrie Publications, Inc & TRO-Ludlow Music, Inc. (BMI), 1936. http://woodyguthrie.org/Lyrics/Roll_On_Columbia.htm Accessed February 14, 2016.